When the Birds Began to Sing

- Nicholas Northwood

- Jul 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

From the Desk of Lord Northwood

July 23rd, In loving him, I became invisible — even to myself.

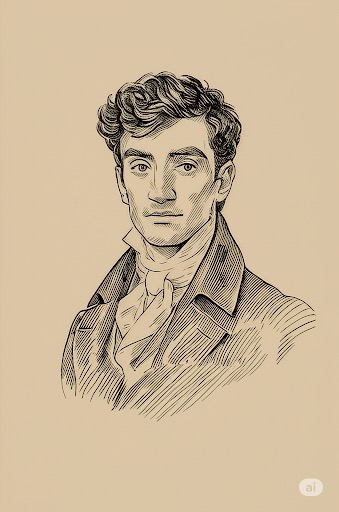

Permit me, if you will, to recount a cautionary tale — one I might have consigned to silence, had it not pressed so heavily upon my chest these many years hence. The gentleman in question shall be referred to, for discretion’s sake, as Mr. Ezra Delrose — a man of elegant bearing and exquisite deception, whose acquaintance I first made during my collegiate years, when youth made fools of us all and hope rendered us blind.

Upon our first meeting, I was struck with that peculiar sensation which often precedes either a great romance or a grand ruin — a sudden, inexplicable certainty that fate had delivered him unto me. There was no earthly logic to it; merely a voice — perhaps divine, perhaps delusional — which murmured that I was meant to know him. And so I did.

We spent that first night together in a kind of delirious enchantment — speaking of dreams, of art, of secret hungers both noble and not. I remember laughter. I remember his fingers wrapped around the root of my desire. I remember the soft chirp of birdsong greeting the dawn as we realised, quite breathlessly, that we had not yet slept. It was, I believed, the beginning of something eternal. I was mistaken.

Mr. Delrose quickly became, in no uncertain terms, the object of my first true and unguarded affection. In a moment of foolish sentiment, I gifted him a silver amulet to encourage his artistic pursuits — the chain upon which it hung once given to me by Miss Cassandra Kerris, a dear companion of my youth, whose friendship, like so many fine things, has since been lost to time and disillusion. I had imagined, naïvely, that such tokens might secure fidelity or invite good fortune. They did neither.

Mr. Delrose was adored by all — or so it seemed. Acquaintances cooed and fluttered about him, ensnared by his charm and his concerted air of melancholy. Yet, once the truth began to emerge, those same tongues grew quite loose. “I never liked him,” they confessed to me in corners and corridors, “There was something off about him from the start.” Even his closest companions were fond of speaking ill when his back was turned. I, in my loyalty, repeated these observations in confidence. He accused me of slander. Such is often the way with men who trade in illusion.

It was after a concert, one I had brought him to alongside my family, that I came across a collection of documents he had most imprudently left out. They bore a name quite different from the one I had known him by — a stage name, he claimed, as though the very foundation of one’s identity might be treated like costume. Further inquiry revealed he had misstated his age by several years and, more significantly, maintained a romantic attachment to a woman of seven years’ standing. “I love her,” he once told me — even as he warmed my bed.

We had, it must be said, rules — though they were his and not mine. I was forbidden from consorting with other gentlemen (on account of “jealousy,” he claimed), though I was permitted to speak to women — ostensibly for reasons of “health.” Meanwhile, he wandered freely beneath the Lavender Veil — that wretched, secretive system of anonymous courtship — and, in one particularly cruel twist, I began receiving messages and parcels addressed to him, misdirected by those who believed I was he. I was a ghost in my own courtship.

He once brought the aforementioned lady — his long-standing paramour — to a gathering at my own home. We got along famously. I was, for one foolish moment, rather proud — convinced he trusted me deeply, perhaps even uniquely. But of course, he didn’t. He instructed me to behave as though she were a stranger. She, ever perceptive, asked why we never spent time together. And I — embittered and exhausted beyond civility — answered coolly, “Ask your beau.”

I gave him so much, dear reader. I escorted him to his lectures, ferried him through the rain, waited at doors like a servant. And in return, he scoffed at any romantic prospect I entertained, declaring none were worthy of me — though he never offered his own heart in their place. He exaggerated his renown as a performer, purchased a following, and, in one particularly grotesque moment, threatened to have me blacklisted should I ever speak of him publicly. This, from a man I had once dreamed of loving out loud.

There was one evening — I recall it with a kind of tremulous dread and carnal fascination — wherein he pressed a knife to my bare chest, the steel cold against the warmth of my skin, and whispered, “Do you trust me?” I was utterly exposed beneath him. I should have said no. But I breathed yes. May God forgive me — I meant it.

He passed on to me, along with his falsehoods, a rather virulent strain of infection that settled in my heart and saw me bedridden for days. Still, I thought of him. Still, I longed.

He had me gather intelligence on “lovers turned liabilities,” whom I later discovered were former paramours discarded with as little grace as I was. His sister once asked me, quite innocently, how our evening of private companionship had gone. I had not been in the same state. It seems he had used my name to mask his dalliances with another gentleman.

That same sister would, in confidence, describe him as the most selfish person she had ever known. When I, ever the fool, repeated this to him in hopes of waking him to self-awareness, he dismissed it as fantasy.

And so the end came. He believed our secret was discovered — and, in a performance more suited to the stage than any drawing-room, hurled my belongings from his window into the night. I sat upon a bench, tears streaming, when Lady Venetia de Canal — newly arrived from some tavern or other — approached with a jest. I called her a whore. The insult slipped out like a match struck in a ballroom — ill-timed, unladylike, and entirely deserved. I attempted to apologise. She forgave me. I remain unsure if I am glad she did.

Later, I wrote him a letter. I accepted all blame — though I held none. We spoke briefly. He was already with someone new.

Years passed. He resurfaced. I, still under some spell, sent him a token of protection — a charm for sailors, to bless his coming voyage. He accused me of harassment, believing I was sending anonymous letters to haunt him. I was not. Perhaps another ghost of his making had risen to do so.

Let this be your warning, dear reader. Ezra Delrose was not a man, but a masquerade. And I — I was merely the fool who mistook the mask for the man.

Faithfully Yours,

Lord Nicholas Northwood